If we were to punt the author from his perch as “solitary hero-creator,” and look at the swathes of people and technology and flora and fauna that networked and threaded together to produce the serial fiction with the author’s name on it … would we find evidence in that serial fiction of the blood, sweat, tears, and grease of those here-to-fore unnamed participants in the process?

I’m going to go out on a limb and say, “Hells yeah.”

As I work on my prospectus for my dissertation – which has the holding title right now of “Dickensian Ghosts in the Machines: Human-Nonhuman Assemblages in the Nineteenth-Century Publishing Industry” – I find myself meditating on what brought me to my current project. What thinking, what books, what people, what environment, led me to need to push back on the “solitary hero” narrative?

My first thought is that (a long time ago) I got very used to being in the corps de ballet. I occasionally got to perform solos, but often, I was a moving part of scenery, setting the stage for the soloists. In the corps, you must function as one – I guess we were Borg-like. You move together, you breathe together. No one person should attract attention. The beauty of the corps is to be living synthesis in motion, to bring the audience into a sublime state of perfect cohesion. I was pretty good at being a dutiful cog in pointe shoes, appreciating the value of obsessive synchrony in order to establish mood and context for the soloists and principals.

It did strike me more than once that the dancers chosen to be soloists were often the people who did not blend in well with the corps. They were good dancers – we were all good dancers – but they were not overly attentive to staying in the lines, as it were. They got promoted; we stayed behind, focusing on our seamlessness.

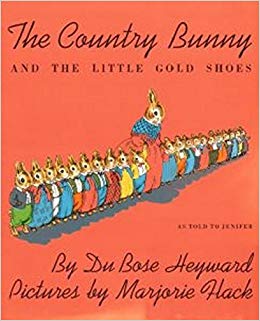

I also see how a relatively obscure children’s book has come to play quite a significant role in my personal philosophy, my teaching philosophy, and now this dissertation. I’m pretty sure The Country Bunny and the Little Gold Shoes (by Du Bose Heyward; pictures by Marjorie Hack) came into my life in the very best way: I think I got to order it on a Scholastic Book Order form when I was in grade school. If you are unfamiliar with this charming little book (I have two copies, actually; I could start a loaning program), this gist is this: a brown bunny from the country, named Cottontail, who is a single mother to 21 bunny children, is chosen to be the Easter Bunny on year, and works harder than any bunny ever to fulfill her momentous tasks. I’m delighted to see that some people have picked this up as a feminist and anti-racist tale (my heart did a flip to see this!), and I certainly agree!

For me, though, the defining moment of the story is the section where Cottontail demonstrates how she can leave her home in the care of her 21 talented bunny children. She argues that her little bunnies work in pairs to complete every necessary household task, and that each task is no less or no more important than any other. This is true of the bunnies who have brooms to sweep the home, the bunnies who make the beds, the bunnies who sing and who dance, and the lone bunny whose job it is to pull out his mum’s chair when it is time to serve dinner.

I internalized the daylights out of this.

I suppose it’s a bit socialist of me, but that wasn’t my thinking at the time (I was, like, 9 or 10). It’s not even exactly my take on it right now. I fell a bit in love with they idea of everyone having a role to play, and everyone having use their unique skills to contribute. The bunnies who played music and the bunnies who danced to that music were as integral to the success of their household as the bunnies who mended clothing and the bunnies who dried the dishes. Every talent is valued and seen as vital to the creation of a harmonious household – so harmonious that Mum Cottontail could change lives and defeat the patriarchy!

So, I like systems of production, where each person and object and element can be identified (even though it may take time) and credited with producing the whole (effect? Object? Experience?). I think a distribution of credit can seem terrifying, but it needn’t be. I’m not advocating for tossing the Dickens out with the dishwater at all; rather, I am interested to better understand how Dickens is part of the assemblage that delivers The Pickwick Papers and Bleak House. I want to set him in the web that also includes points on a map indicating other actants: where a laborer is collecting esparto grass to send to the paper makers to make their products cheaper, and where the enslaved people in the American South pick the cotton that gets shipped to England as a raw good for processing. What if those lines of production did not radiate from one fixed point (Dickens) but, instead, intersected with each other and through Dickens, bursting through him in the form of the fictions published serially?

Right now, this image, in my mind, is a bit more extreme – rather than a tree breaching the soil, I’m thinking of images of the zombie fungus that bursts through ants. Bit violent, but perhaps it has merit.